By Ilja Kamerling

UCR Class of 2014

Although I had wanted to participate in the Going Glocal Mexico project from the moment I had heard about it, it hurt a little inside when I booked my tickets, since I realized that I would miss out on a summer full of great festivals. It turned out that I didn’t need to worry; the program brought us to one of the most special festivals we are likely to go to in our lifetimes.

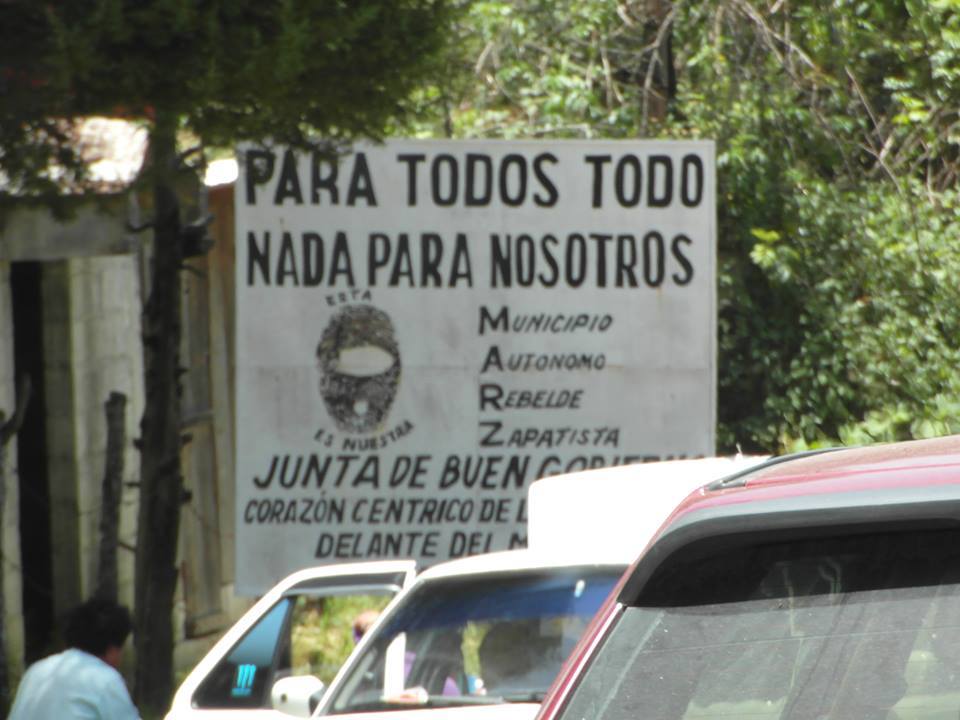

As part of the field trip we visited the Zapatistas festival in Oventic, a small place in the state of Chiapas. It is also the central location of government, if you will, for the entire Zapatistas territory surrounding it, bringing us to the center of one of the movements, which had had most of our attention so far.

But for those of you a little less tangled up with sociology, let me explain the Zapatista movement first. The Zapatistas, or the Zapatistas National Liberation Army (abbreviated in Spanish EZLN) became known after 1994 when they seized the city of San Cristobal and declared war on the government of Mexico. The movement came forth out of a rebellious group, which had been training for a guerrilla war in the mountains. This group stood up for the rights of local and indigenous people, and for the land rights of the small peasants; groups they say were not heard by the government.

The Zapatiatas are focused on  remaining local. They oppose globalization as they find that people cannot be seen outside of their context. Therefore global systems are fallacious because they are in no way capable to include all different contexts of people worldwide. Furthermore the Zapatista movement strives to organize in communities, focusing on communalidad, the sense of community, as the most important sense of being.

remaining local. They oppose globalization as they find that people cannot be seen outside of their context. Therefore global systems are fallacious because they are in no way capable to include all different contexts of people worldwide. Furthermore the Zapatista movement strives to organize in communities, focusing on communalidad, the sense of community, as the most important sense of being.

This can for instance be seen in their “bottom-up” way of doing politics. The job of governing is integrated in the daily decisions of a community not as a prestigious position, but as a task towards the community. They also consider the assembly of the whole community the highest organ of decision-making. Compare that to our politics; think US politics, Obama or even the Netherlands and Mark Rutte, and you can see where the label ‘rebellious’ comes from.

Another focus lies on the autonomy for every person; as for instance explained through the assembly, decisions should according to them be taken with each other instead of over each other. This also has its effect on the position of women in the communities, which is just as important as that of men, and the position adults hold towards children.

After twelve days of war in 1994 a ceasefire was established between the EZLN and the Mexican Government under guidance of Catholic Bishop Samuel Ruiz. According to Sub-commandant Marcos, the spokesperson of the EZLN, this ceasefire was not agreed upon because of any demotivation for their cause, but because they were bound to the demand of the people and the people wanted an end to the fighting and bloodshed. The peace however was unstable and in later years clashes have still taken place between Zapatistas or their supporters, and the government and paramilitaries.

Through years of unconventional activities by the EZLN, such as marches to Mexico City or an unexpected silent protest, still being unable to reach a solution together with the Mexican government, the Zapatistas have formed over 30 communities living together in an autonomous area in Chiapas.

These communities would be governed on daily basis by five ‘Juntas de Buen Gobierno’, councils of good government, that consist of ordinary men and women who are chosen to do this task for a year. Their motto is to govern by obeying the demands of the people, and the goal is to set up communities without any sense of hierarchy. To be able to establish this horizontal governing structure, the military side of the movement has withdrawn into the mountains since 2003 and makes no part of the Juntas or communities itself. This withdrawal was justified by the belief that an army was always hierarchical and as the people of the army did not want to hinder the development of a horizontal community they pulled themselves back. Since that moment the Zapatistas communities have been very internally focused and, in a way, more closed off towards the outside world.

That is, until this summer when the tenth anniversary of the existence of the Juntas was celebrated in a very special manner. A two-day festival was held after which an Escuelita would start, a school in which Zapatistas would teach and discuss topics such as freedom, autonomy, and emancipation with 1500 eager participants from around the world. As the Going Glocal group, we were invited to be a part of the Festival, through the connection with Gustavo Esteva, granting us a look into these peoples’ lives and their ideas, which was a one-time opportunity.

Meeting this group of people from  whom we had learned so much already was a very special experience for most of us. A good example of this was confrontation with the feeling of for once being the outsiders, a role that normally in festivals or in any touristy place is reserved for people from non-western cultures. It could also be seen in our first hesitations or awkwardness in meeting with people wearing ski masks, a symbol for the egalitarianism of the movement and the visibility of the people behind, although we had discussed this symbol for so long already.

whom we had learned so much already was a very special experience for most of us. A good example of this was confrontation with the feeling of for once being the outsiders, a role that normally in festivals or in any touristy place is reserved for people from non-western cultures. It could also be seen in our first hesitations or awkwardness in meeting with people wearing ski masks, a symbol for the egalitarianism of the movement and the visibility of the people behind, although we had discussed this symbol for so long already.

However, the visit was certainly not only heavy or difficult, but fun as well. The first day was marked by a lot of raining and dancing. We all talked to different people and some of us even connected to the children of the village and started dancing with them. We noticed that as largely Western-oriented students we had a biased perspective, since, until it was pointed out, we didn’t realize that the equal participation of women and their unashamed behavior was something special. Some of our group stayed for the night and were there to witness speeches delivered by the EZLN and the dancing at the enormous party that followed.

The second day we saw the aw arding of the prizes for the sports tournament that had taken place at the festival. We watched performances of all the different communities, and heard speeches of different people from the Juntas; sometimes in Spanish and sometimes in an indigenous language that none of us could understand. We danced with the kids again and lost some shoes in the mud. It was a festival, and it might not have been the actual happenings at the festival itself, but to see the people who make the Zapatistas, to see those who are living what we have merely learned about, that was something I gladly traded my festival summer for.

arding of the prizes for the sports tournament that had taken place at the festival. We watched performances of all the different communities, and heard speeches of different people from the Juntas; sometimes in Spanish and sometimes in an indigenous language that none of us could understand. We danced with the kids again and lost some shoes in the mud. It was a festival, and it might not have been the actual happenings at the festival itself, but to see the people who make the Zapatistas, to see those who are living what we have merely learned about, that was something I gladly traded my festival summer for.

Ilja Kamerling, class of 2014, is a History and Sociology major from Heerjansdam, The Netherlands.