By Rebeccah Steil

Current Events Section Editor

Art thieves are viewed with a mixture of frustration and fascination. The fascination can be seen in shows such as White Collar, where a former convict spends multiple seasons of the show trying to obtain a Nazi submarine full of stolen art, while wearing an impeccably tailored suit and charming the FBI. Frustration can be seen in the outcry that occurred after the Rotterdam Kunsthal museum robbery, which included the theft of works by Monet, Picasso, and Matisse. Although the suspects were apprehended, the paintings have not been recovered and may even have been burned to cinders.

Art theft has been a problem for many years, but the act was at an all-time high during WWII. Jews were coerced to give up art collections or sell them for a pittance, as their right to won them were revoked in most Nazi controlled countries. Owners of contemporary art, deemed unsuitable by Hitler, were also stripped of their paintings. The question of ownership has never really been fully answered, as the paintings have often switched hands multiple times since the Great War and can make tracing ownership tricky.

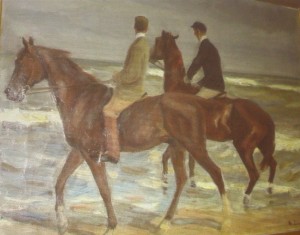

However, the situation of Cornelius Gurlitt is fairly straight-forward. At the beginning of November it was released that the son of a Nazi art dealer was in possession of 1,406 paintings and drawings, collectively valued at €1 billion. At least 590 of the pieces, seized by German authorities, are believed to be art looted by the Nazis. The contemporary art considered “degenerate” (200 pieces) were sold to Gurlitt’s father for 4000 Swiss Francs from Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels.

The difficulty all of this knowledge being public will pose for Gurlitt has already been made apparent by the problems he faced trying to sell just one painting in 2011. Gurlitt had to reach a settlement with the heirs of a Jewish art dealer, after they presented compelling evidence that the Nazis stole Max Beckmann’s “The Lion Tamer”. Hildebrand Gurlitt, Cornelius’ father, claimed all the paintings perished in the Dresden bombings during the war, which allowed the family to avoid scrutiny until now. The demands being made now are for the German authorities to disclose which artworks were seized.

Another matter entirely is that of restitution. Some descendants of owners have clear evidence proving a valid claim to the painting, and that cannot be ignored. Unfortunately, the limits for the return of work have expired in Germany. Those seeking to reclaim pieces will have to do so with the aid of a US court or appeal to Gurlitt’s morality. Gurlitt might be charged with embezzlement and tax evasion, which would be difficult to prove as the crimes happened so long ago, not to mention the statute of limitations that would apply. The complicated mix of restitution and property law will make this situation difficult to resolve legally, let alone the affect it will have on Gurlitt’s reputation.

This affair has been a reminder of how difficult it is to trace ownership and the wounds stolen artwork can inflict. The aforementioned case is an example of how we perceive art theft as frustrating, as hoarding art is not a solution, but neither is the impending legal campaign that will soon start.

Rebeccah Steil, Class of 2014 is a Law and politics major from San Antonio, Texas, United States

Source: Der Spiegel