Julie Airey

Staff Writer

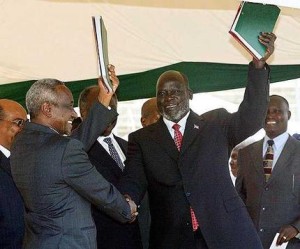

Ten years ago Sudan signed an historic agreement during a special meeting of the United Nations Security Council, with the aim of ending the civil war in the Sudan by January of 2014. The leaders of the factions involved in the conflict, Vice President Sudan Ali Osman Mohamed Taha and leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, John Garang, signed the agreement.

At that time, a civil war had been raging between the Sudanese government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement for 21 years, making it Africa’s longest lasting civil war. The civil war, often called the Second Sudanese Civil War, lasted from 1983 to 2004, and was preceded by the First Sudanese Civil War, which ravaged the country from 1955 to 1972. All told, thirty-odd years of conflict had consumed the country and raised doubts in 2004 on whether the agreement could lead to a sustained peace. As the tenth year anniversary of the agreement is celebrated in 2014, South Sudan has succeeded in some regards, but the region is now largely unsafe as a new conflict engulfs the countries.

The treaty outlined several conditions necessary for pea ce, namely that: the south of the country would be granted autonomy and would hold a referendum in 2010 to consider reunification. The treaty further stipulated that if the referendum chose reunification, the armies of both government would be permanently merged. Providing for economic security, the treaty ordered that during the six year period of separation both parts of the country would split oil revenue. Lastly, the treaty provided that Islamic Shar’iah Law would be implemented in North Sudan, whereas South Sudan would later determine the foundation of law with an elected assembly.

ce, namely that: the south of the country would be granted autonomy and would hold a referendum in 2010 to consider reunification. The treaty further stipulated that if the referendum chose reunification, the armies of both government would be permanently merged. Providing for economic security, the treaty ordered that during the six year period of separation both parts of the country would split oil revenue. Lastly, the treaty provided that Islamic Shar’iah Law would be implemented in North Sudan, whereas South Sudan would later determine the foundation of law with an elected assembly.

In order to assess Sudan’s progress, the developments in the last decade can be compared with the conditions in the agreement. The six year partition of the country ended up lasting indefinitely and was maintained in the new agreement in 2011. The initial referendum had several obstacles, such as fragmented rebel forces threatening potential voters, the questions of whether refugees would be allowed to vote, and if they were, would their vote count for the North or the South? Yet, despite these obstacles, the referendum was characterized by a shocking 95% turn-out of rate, of which only 3% were in favor of unification. Further indicating Sudan’s (the North) wish to respect the secession, the referendum led to the peaceful dismantling of the Joint Integrated Units, the unified military arms of North and South Sudan.

North and South Sudan have also made progress in the broader scope of recovering from the effects of the long-lasting conflict. After the peace treaty, rebels groups came to an agreement to demobilize all child soldiers by 2010, which according to both North and South Sudan, has been done. South Sudan made the admirable move of launching a Quarterly Statistics Report in 2012, in order to gain an overview of crime in the young country to begin draft policies to combat it. According to the most recent report, South Sudan struggles with crime disproportionately affecting women, but there has been an overall decline in major crimes, such as murder, kidnapping, arson and rape.

Unfortunately North Sudan, now referred to as The Republic of Sudan, faces an internal civil war in the region of Darfur. This conflict has lasted since 2003 has not yet been resolved. In light of this conflict, although the current relations between the south and the north adhere admirably to the original peace agreement of 2004, enough tension remains in the region to indicate that the two countries are still a long way from peace and stability. The next ten years may lead to new developments between the two countries, but for now both have been able to coexist mostly war free.

Julia Airey, class of 2015, is a Law and Linguistics major from Ashby, Massachusetts, United States.