By Anonymous

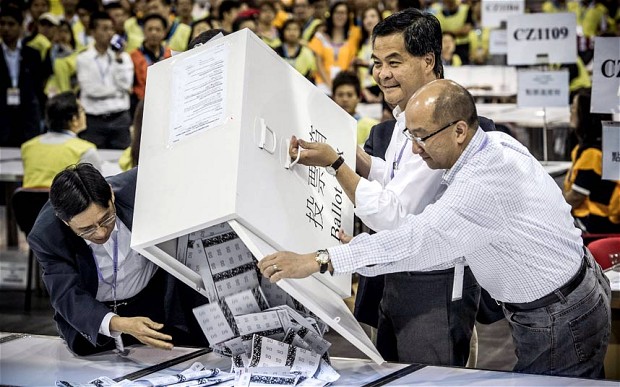

Recently there have been reports about numerous protests in Hong Kong concerning a controversial decision that has been made in Beijing: the central government has issued a statement regarding Hong Kong’s 2017 elections, namely that all the candidates must be approved by a committee beforehand, and that the Chinese government is choosing the members of the committee itself. After all, this means that there will be no free elections in Hong Kong, and that mainland China is tightening its grip on the traditionally liberal financial hub of the East. But in order to fully understand the scope of this decision one needs to look back to the history of Hong Kong’s independent status and relation to China itself.

After four years of Japanese occupation during the Second World War, Hong Kong had been handed back over the United Kingdom as its Crown Colony. Then, after two decades of consistent modernisation, Hong Kong’s economy flourished and it had been declared as a special economic zone by the Chinese government, which feared that more restrictions would hinder Hong Kong’s development – the area remained under British authority with a more or less independent leadership in form of a local Chief Executive.

The crucial point in the city’s history is, however, the year 1997 in which Hong Kong’s sovereignty was returned to China after approximately 150 years of British governance. At that time, there were many optimistic voices that predicted a positive influence of Hong Kong’s liberal economic structure on the politics of continental China, since Hong Kong had been granted another 50 years of semi-independence as a Special Administrative Region (SAR) including its own currency and taxation. Some important questions emerged at the time: Is Hong Kong becoming more international, or more Chinese; is it having a liberating influence on China, or is China bringing Hong Kong under its authoritarian rule? The Economist predicted the former, Fortune Magazine declared Hong Kong’s ‘end’. One can say now that both more or less missed the mark. At many points in history following Hong Kong’s handover it was feared that the end of Hong Kong’s tradition had indeed arrived, be it the bird flu, SARS, a financial crisis, or an attempted security bill called Article 23 concerning the establishment of anti-subversion laws – the city seemed to have run out of luck many times. Nevertheless, it persisted, and has continued to evolve to become one of the most crucial and vibrant financial centres around the world. Furthermore, it should be noted that Hong Kong was, also under British rule, far from a liberal democratic system – in that sense the fact that there are elections at all can be seen as a huge leap forward.

For the future of the city, despite changing forms of governance and legislation, one can say one thing for sure: namely that Hong Kong will most likely always remain a unique spot in China’s landscape due to its great economic value – not least because many citizens of Hong Kong have made big investments into Chinese companies – something that the government in Beijing knows all too well.