By Gabrielle Gonzales

Earlier last week, adolescent millennials and millennial adolescents alike mourned the end of the eight-year ten-season strong run of Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time. Why that matters continues to be a topic of interest among Film and TV critics across the world and of all ages; after all it isn’t a title that resounds “the canon of 21st century television”, as James Poniewozik aptly points out. Still, the beloved inhabitants of Ooo have been and continue to be icons of today’s poptimistic culture.

The thing about Adventure Time is that the generation that makes up much of its demographic (despite it being aired on Cartoon Network) – millennials – did not grow up with it in the same way they did with Harry Potter; they grew into it. While it may not hold as such particularly among the UCR student-body, there is still good reason to consider why it indeed shook a good portion of “us” to the core upon hearing about its end. Much like the Harry Potter saga, many if not all of us hold close to our hearts, Adventure Time went through much of a similar organic development from pilot to finale, using the same voice actor(s) and essentially allowing its audience to follow the lives of Finn the Human and the Human voicing Finn, as well as appealing to the binge-watchers in all of us. The parallel does not end there: senior millennials, who themselves have children growing up with it in the same manner, have also pointed out how the series got darker as it progressed through the eight seasons (which, if I may add, is also reminiscent of HP’s eight-installment film franchise).

The show is by no means realistic but is notable for being one of those shows that got real real at times. Elastic dogs and candy people aside, the animated kids’ show was known for bringing to its rose-coloured surface its more mature undertones. Airing on Cartoon Network for the first time in 2010, the show takes place amid the ruins of the Great Recession. While it could all just be perfect timing, the series aligns itself with history – its plot diverging with our own towards the end as the land of Ooo is revealed to have suffered through the “Mushroom War”. Likening the financial crash of 2008 to a fictional war (which some have interpreted as a possible nuclear warfare) may seem like a stretch but Adventure Time does not just function as an allegory for history; it has, in its own albeit surreal way, served its cathartic purposes for a generation whose personal, social and professional sense of progress in this Mushroom-waresque-ridden world seems to have been stunted and now experience what some have termed “extended adolescence”. Much like Finn the Human, a remnant of the past world, Adventure Time’s older audience have been left wandering and floundering around trying to navigate themselves in the world and life in general.

This phenomena doesn’t just manifest in Adventure Time; you can and would have seen it in most sitcoms that aired around the same time like New Girl and Brooklyn Nine-Nine whose adult protagonists bear more resemblance to Spongebob than Seinfeld. What distinguishes Adventure Time, apart from its being animated, is that it did more than expose the existence of such an “extended adolescence” – it embodied it. Being a cartoon series, the show assumed a role similar to most things millennials would have watched throughout their childhoods – just that, this time, the appeal is in its coming-of-age quality, not so much the fantasy and escapism. Poniewozik recounts one especially poignant scene in which Jake notices his landscape-painter brother Jermaine has shifted to increasingly abstract pieces. Disturbed and determined, Jake sets out to find answers, only to be reassured by his brother: “I painted so many landscapes that the shapes of the land began to lose their meaning… The shapes broke apart for me, so I painted them like that. And it’s not like my new paintings replace my old paintings. They’re both me.” A bit heavy for minors, but essentially so – and all the more relatable for anyone whose own coming-of-age might be experiencing a delay.

Apart from its emotional quality, the show earns its renown for markedly ushering in a renaissance age in cartoon tv shows. At a time when nostalgia seemed (or still seems) to be in, Adventure Time became a monument of a generation’s dearly-held past – only it has the added effects of having a certain degree of wokeness. While it probably will not dominate discussions of high culture, it is hard to deny its revolutionary role in TV history, from developing a cult-like following across different ages to inspiring a long string of animated shows (see: Steven Universe, The Regular Show, We OK K.O!, Over the Garden Wall, Rick and Morty), of which many owe their entire existence to its conception. So, naturally and understandably, it has been a painful farewell for many, but for those well acquainted with childhood goodbyes, it only serves to remind us that the fun never ends.

Gabrielle Gonzales, Class of 2020, is an Art History and Literature Major from the Philippines.

Sources:

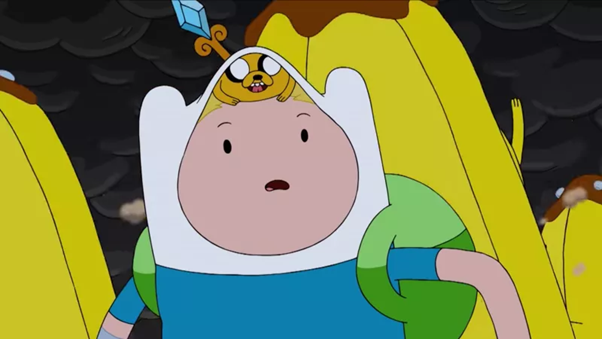

Image Source: Finn and Jake getting ready for war in the series finale, “Come Along With Me” (Cartoon Network (YouTube)

Poniewozik, James. “‘Adventure Time,’ TV’s Surreal Masterpiece, Comes to an End”. The New York Times (2018).

“Come Along With Me.” Adventure Time (2018). Cartoon Network.