by Jedidja van Boven

The Bellingshausen station, a Russian outpost on King George Island, Antarctica, doesn’t exactly make headlines often. However, when researcher Sergey Savitsky, stationed at the isolated facility, was charged with attempted murder of a colleague last week, the media started paying attention to the most remote location where crime reports could possibly sprout from. The attack was the result of an emotional breakdown after prolonged isolation, as the culprit had been living with the victim for six months in complete solitude. Though the victim was only injured and the culprit voluntarily surrendered to authorities, the incident begs the question: how are crimes handled in environments where sovereignty is muddled, natural conditions are harsh, and winters are excruciatingly long?

Antarctica faces crimes occasionally, despite not having a permanent population. Alcohol abuse, fighting, and indecent exposure (brrr) are not uncommon. For minor offenses, perpetrators are fired and sent home as they are subject to their home country’s jurisdiction. Station managers in Antarctica are trained to deal with evidence and arrests, and culprits are confined to their hut after being arrested- after all, there aren’t many places to run to in the continent that is blanketed in ice year-round.

In more serious crimes, however, the question of territorial sovereignty becomes difficult, as several countries claim ownership of different parts of Antarctica. The most famous example of this was the Rodney Marks case from 2000. Marks was an Australian astrophysicist who worked on the Antarctic Submillimeter Telescope for a research project. While stationed in a US-run base that was located in New Zealand-claimed territory, he suddenly fell ill and died. Marks’ body was transported to New Zealand for an autopsy, where he was confirmed to have died from methanol poisoning. Marks was a newly engaged, young PhD researcher with nearly-finished academic work; therefore, suicide was quickly ruled out as a possibility. He had a mountain named after him- but the case remains unsolved as the only potential murder ever in Antarctica.

Another unique case study is Iceland. The Scandinavian country is generally deemed very safe; it has no army and its citizens ‘’police themselves’’. Social cohesion among the small population comes from the necessity to look out for each other during the unforgiving winters in the North. Iceland encounters few problems with crimes like murders, save for one exception: disappearances.

Since 1930, between 70 and 80 Icelanders have disappeared into thin air, a phenomenon some have attributed to Huldufólk: the mythological elvish people that are believed to live in the hostile interior of the island. Mythological or not, it is established that the disappearances are more often linked to natural conditions than to people.

There remains one glaring anomaly.

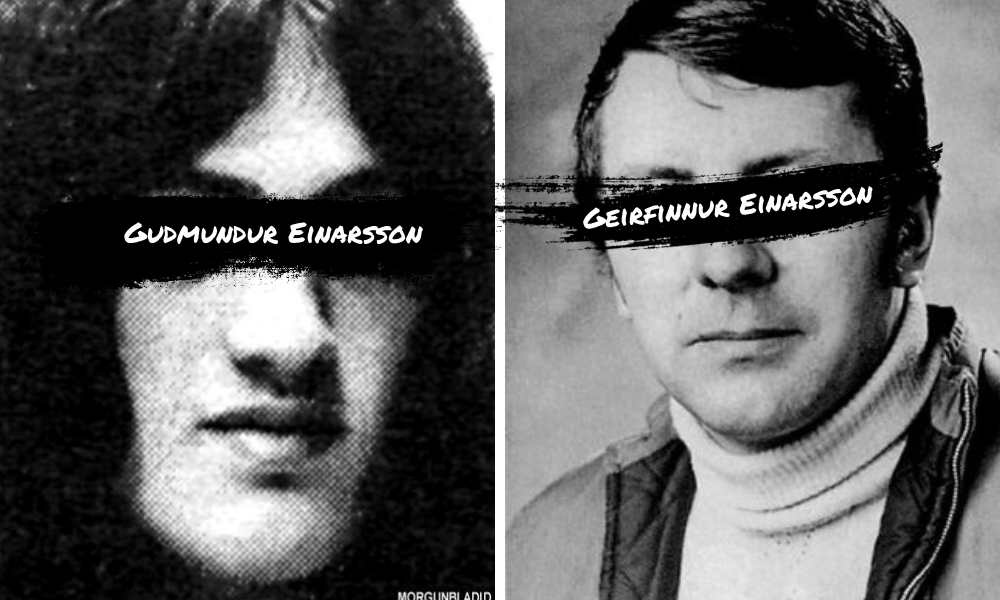

1974 is a year that marks the history of the Icelandic police to this day. Early in the year, an 18-year-old man named Gudmundur Einarsson disappeared in the middle of the night when he was walking home from a party alongside a poorly lit road in a remote region. With the frequency of disappearances, neither media nor police paid much attention to it- until 10 months later, when 32-year-old Geirfinnur Einarsson (the two are not related) also disappeared without a trace. The police was suddenly under immense pressure from the public to solve the cases. However, a lack of evidence caused the investigation to be wound down in 1975.

Soon thereafter, the police caught word of a foreigner who had something to do with the disappearances: the Polish Saevar Ciesielski, alongside his girlfriend Erla Bolladottir. After questioning, Erla claimed to remember not only voices on the night of Gudmundur’s disappearance, but also to have seen the murder occur around the house she shared with Ciesielski. Despite Erla’s uncertainty in distinguishing reality and imagination and her disbelief in her own involvement, the police managed to arrest several of Ciesielski’s friends, all three of which eventually admitted to having killed Gudmundur.

Thinking the group may have had something to do with Geirfinnur’s disappearance as well, the police questioned them again in 1976. This time, with the help of renowned German detective Karl Schutz, a sixth person was arrested: Gudjon Skarphedinsson, who also admitted to murdering Geirfinnur. Erla Bolladottir was last in confessing, confirming that the group had killed the man and buried his body in the uninhabited lava fields.

Something was off about the investigation. There was no physical evidence to suggest that the six had been involved in either of the disappearances, yet all of them confessed. The inconsistency started wringing when in 1977, a verdict was about to be given and each of the suspects tried to retract their confessions, saying that they were false.

How could six different people not remember a serious crime and still confess to have committed it? Gisli Gudjonsson, who worked on the case in the 70s and is now a famous forensic psychologist, explains it as ‘’memory distrust syndrome’’: isolation, high pressure, and false evidence can cause innocent people to believe that they are guilty. This idea was worsened by the police forcing one of the suspects, Kristjan Vidarsson, to reconstruct the murder, effectively making this simulation seem like reality. Also, the Icelandic police were later found to have threatened Cielsieski with drowning if he didn’t confess to a crime he didn’t commit.

The case was reopened in 2011 to investigate these practices. An important piece of evidence of questionable police behavior was the diary kept by one of the suspects, Tryggvi Leifsson. When this diary was analyzed, it was clear to investigators and psychologists that the accused group should be deemed innocent. The police was under so much pressure to solve the strange cases that they made a few petty criminals believe they were dangerous murderers. The case was a major blow to the credibility of the Icelandic legal system. Last month, five out of six suspects were acquitted by the Supreme Court, with the sixth- Erla Bolladottir- still fighting to have her conviction overturned.

There might be a reason why so much of crime fiction is set in Scandinavia and other remote places- some cases suggest that the eternal winters and apocalyptic environment of these locations contribute to the frequency of disappearances and the difficulty in solving them. And, as it turns out, even the most utopian societies can harbor dark secrets.

Jedidja van Boven, Class of 2020, is a Politics, Law, and Anthropology major from Oosterwolde, The Netherlands.

Sources:

Featured Image Source: https://m2.mbl.is/48-VFuMQeSBN3hkEYSh7bNoZDpM=/320×480/smart/frimg/9/2/902438.jpg

Image Embedded in Article Source: https://news.files.bbci.co.uk/include/shorthand/42193/media/ch1_victim_gudmundureinarssoncredited-mr_iw6jhx1.jpg

Cox, S. (2018). The Reykjavik Confessions. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/the_reykjavik_confessions

Man faces attempted murder charge after stabbing at Russia’s Antarctic outpost. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/oct/24/antarctic-stabbing-attempted-russia-outpost-man-charged

Rousseau, B. (2016). Cold Cases: Crime and Punishment in Antarctica. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/29/world/what-in-the-world/antarctica-crime.html

Serena, K. (2017). The Mystery Of The South Pole’s Only Murder. Retrieved from https://allthatsinteresting.com/rodney-marks

Þórsson, E. (2017). 70-80 People Have Vanished Without A Trace In Iceland Since 1930. Retrieved from https://grapevine.is/news/2017/10/18/70-80-people-vanished-without-a-trace-in-iceland-since-1930/