By Tsjalline Boorsma

UCR Class of 2016

This Spring Break, most UCR students left Middelburg to enjoy the delights of other cities. Some, however, were here on the 19th of March to vote in the municipal elections. Every four years, the citizens of Middelburg get to cast their ballot and with that action, decide what change they champion. All students with a European passport were also eligible to cast their vote and decide alongside the local citizens. The parties that win the election with the majority can decide on issues relevant to students such as whether supermarkets can open on Sundays, whether coffee shops will be allowed in town, and to which degree the arts and cultural activity in Middelburg will be supported by the municipality

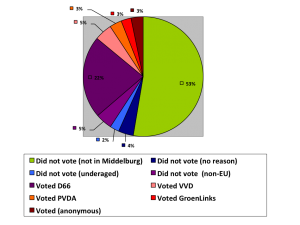

As the election is also fundamentally important to the everyday life of students, I conducted an opinion poll on Facebook to gauge the voting behavior of participating UCR students. As can be seen from the pie chart, the majority of students did not vote because the elections were held during the spring break, while many students were not in Middelburg. There were also a few students with European passports who could not vote because they were underage.

Another reason why some students could not vote was because they did not have a passport from one of the countries in the European Union. For example, a fellow student and national of Singapore, Kirin Heng, received a voting ballot, even though she was not allowed to vote. We started discussing the contending parties, but then we discovered that it was not even possible for her to vote. Foreigners from outside of the EU have to reside here in Middelburg for five years to be eligible to vote in municipal elections.

This might be disappointing for those unable to take part, since the elections were quite unique this year. One of UCR’s own students, Jurian Bazen, participated in the elections as a candidate for D66, a social-liberal party. Many of the students who voted cast their ballot for him. “Normally I do not vote D66, but I thought that having a student in the municipality council would be good. Unfortunately it did not turn out that way”, said third-year student, Ilja Kamerling.

Asking students about their reasons to vote in general, Kira Lemgau stated that she voted because she thinks democracy is important. Richy Den Toom, who voted for the liberal party VVD, said, “If you don’t vote you have no right to complain about decisions. Also it is one’s civil duty to partake in the democracy.” Cathelijne Beens, who voted for ChristenUnie, remarked, “Voting is both a right and an obligation. People died in the past fighting for the right to vote. The least we can do these days is go there and tell the government what we think.”

Upon receiving my questions on his reasons for voting, Ivar Troost responded with a short essay on politics. Ivar said: “We might not live in a perfect democracy, but we do live in a representative democracy. As with any type of democracy, this system can only work if all people actually vote. Otherwise the voting minority would have the power, instead of the majority. Voting in the municipality elections is the only way in which we can challenge the often top-down approach of our national government; to show that the Middelburg community has a voice and a valid opinion. We can be the test bed for innovation, or the showcase of tradition.”

In Middelburg, 59% of the citizens who were allowed to vote actually did vote. This percentage is considerably higher than the national average, which was 53% this time. The party that most students voted for, D66, was also one of the most successful parties in the elections across the Netherlands, together with the socialist party SP. They respectively received 2.9% and 3.4% more votes than in the last municipality elections of 2010. The parties that are currently in the national government, VVD (the liberal party) and PVDA (the labour party) suffered a considerable loss of respectively 1.9% and 2.98%. Nevertheless, the PVDA continues to be the biggest party in Middelburg, followed by the Christian party CDA and the local party LPM. Lastly, a party that is small in the municipality elections, but received a significant amount of votes from UCR-students, is the green-social party, GroenLinks. Unfortunately for those students, they have suffered a tremendous loss of 6% of the votes since 2010.

As mentioned before, the significance of the municipal elections to UCR is undermined by the mere fact that a significant portion of the population is unable to vote. However, this trait will not change the fact that those chosen as a result of these elections will make decisions that bind all in Middelburg. UCR students whom were unable to vote are not left without remedy. Voting is merely a part of conventional political behavior. For those left without a vote, non-traditional political activity, such as protests and rallies leave room for change. With enough students supporting a change, Middelburg could even set a precedent in the Netherlands, by allowing foreigners registered in the municipality for less than five years to vote. But for now, students can try to influence the city in many other ways. The mere presence of a unique and multicultural student population has made Middelburg a different city than it was a decade ago. Although not all of UCR’s voices are heard in the elections, at the very least they are heard on the streets of Middelburg, where they can make a change.

Tsjalline Boorsma, class of 2016, is a Philosophy and Anthropology major from Groningen, the Netherlands.