These students tried to take notes during a history class, but what appeared on the board will shock you!

Forget Rembrandt van Rijn’s Night’s Watch, forget Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with the Pearl Earring. The Dutch master painters of the Golden Age can eat their heart out over this monumental piece. Because lo’ and behold before ye, students of UCR; an original piece by our own Dutch master and history lecturer: Tobias van Gent. This faculty member can be found strolling around proudly anywhere between Eleanor and the A Domani ice-cream counter, and can be recognized by carrying five books under one arm and a Pepsi cola in the other.

This week, I am very proud to present to you a concise analysis of this classic ‘marker-on-whiteboard’ piece from 2016 named Age of European Expansion. And with me being a history major and all, I’ve encountered Van Gent’s homework assignments for at least 20 times already; his first question will always be for us to provide a historical background with the source. So that is exactly what I will do first.

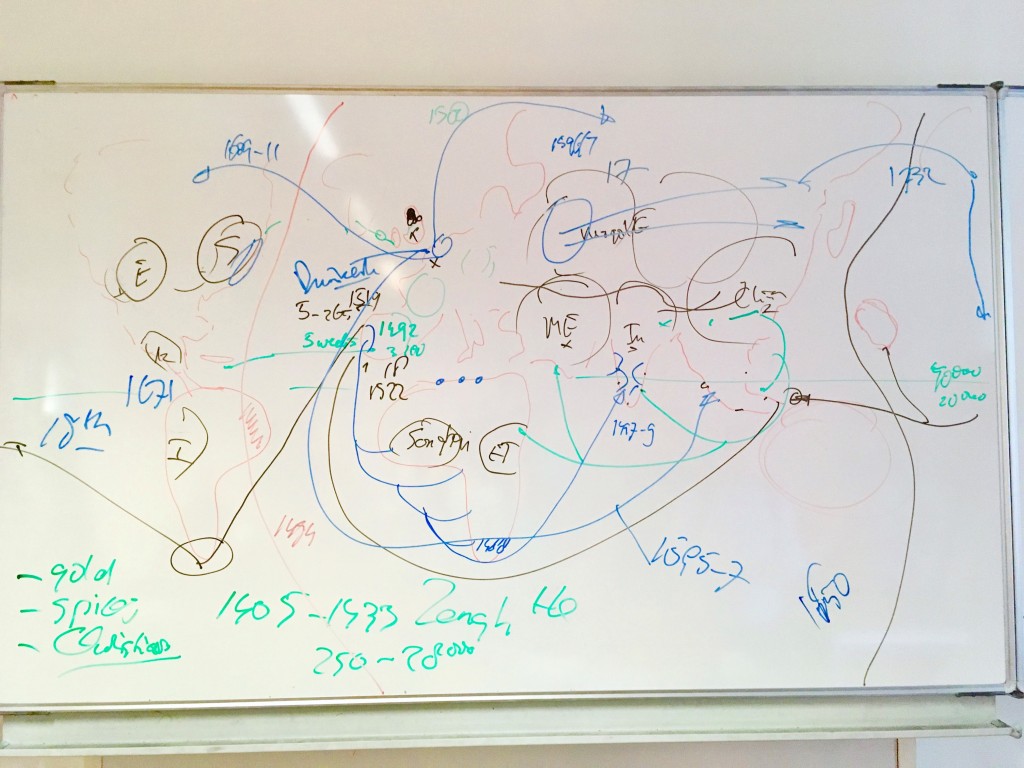

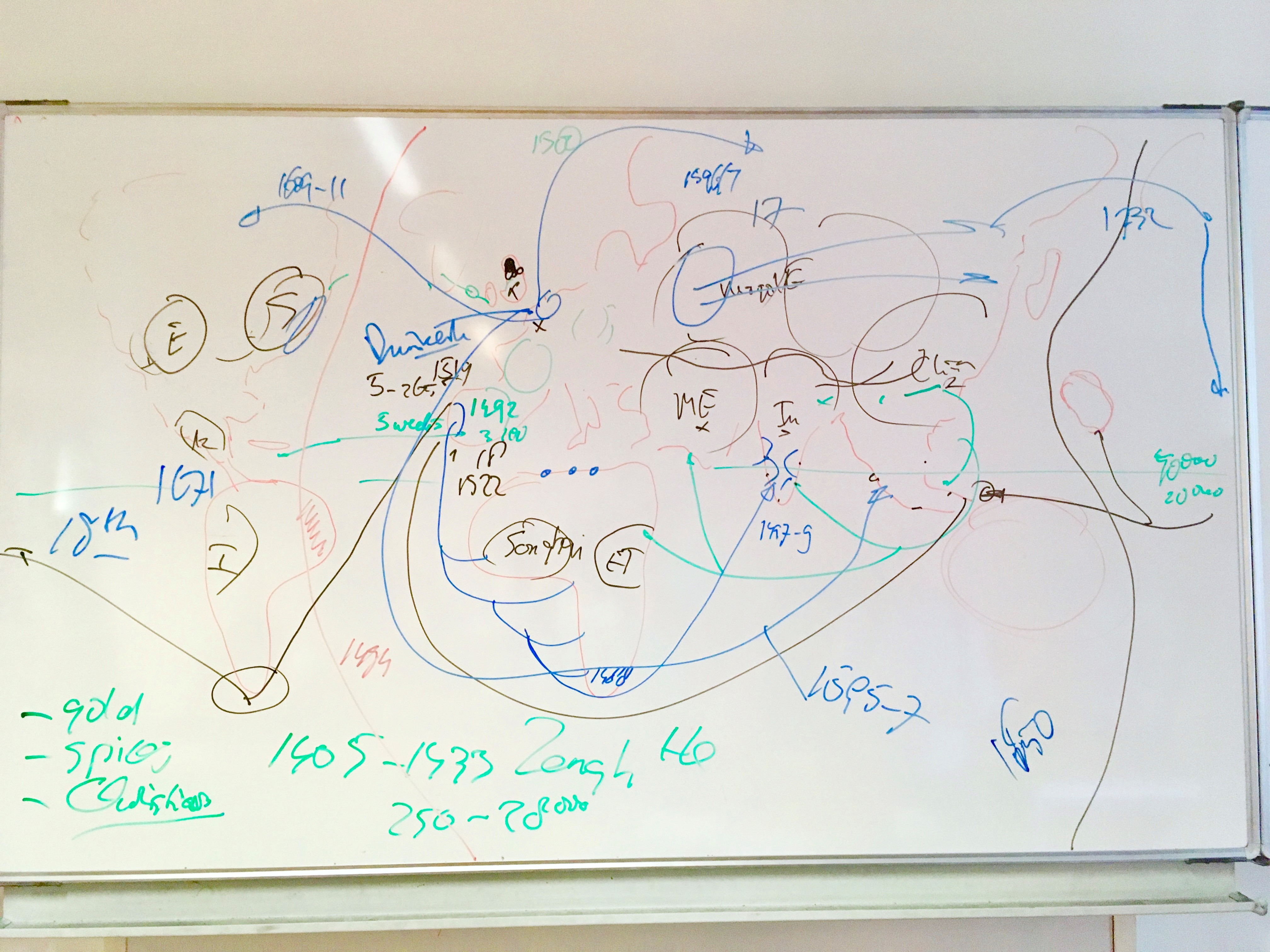

According to Wikihow, the first result that popped up during my Google search on how to critique artwork, one must provide an ‘artistic summary’ in order to better understand the history and influence of a painting. Step one for such a summary is to state the situation surrounding the artist and his contemporaries as they did or saw the piece. Well, the creation of this gem was witnessed by a university class of first, second and third year students. They all saw the moment that Van Gent was hit by inspiration and ran to his cup of whiteboard markers, where he chose one of his nearly empty professional pencils in the colour Demolished Rose to set the base for his painting. As you can see in the picture above, this vague colour appears to form several semi-geometrical shapes in the background. After the professor deemed his framework finished, he slowly turned around and informed the class that he had just drawn a map of the world. A few panicked looks were exchanged, but there was no one who dared to make a comment under the Van Gent Classroom Regime.

Step two requires us to state the influence the artist was considering while doing the piece. It is now known that the Professor aimed to present us with a visual representation of the most important colonies and trade routes during the European expansion roughly between the 14th and 18th century. However, at that time, the only influence that his work produced was to make people doubt the life’s choices that led them to sit in that class at that particular moment.

Another step is to “explain how the details of the piece come together through some sort of atmosphere and principles of art in order to symbolize or capture the strongest essence of the subject.” Now believe me when I say that I have tried my very best to interpret how the details of this work came together, and how the in-class atmosphere changed while it did, but after several wasted hours it came to me that the only way I could capture the essence of what this piece did to those who witnessed its birth, was to bring in the heavy artillery of anonymous reports. Ha!

Thus I started an investigation. I asked my little birds to whisper to me their feelings about the art that Van Gent had produced right in front of their eyes. I received wonderful data in the form of quotes and metaphors, which I shall now incorporate into this analysis.

According to the next step in the analyzing process, one now answers questions about how the piece comes across to you as an interpreter. Therefore, one of the questions I asked my informants was to describe their feelings about taking notes from Van Gent through a song title. One of them immediately suggested Genesis – Land of Confusion, followed by a slightly desperate Ne Me Quitte Pas from Jacques Brel. These answers suggest that the atmosphere surrounding the artwork can be interpreted as a little…angsty. I received another great report that might illustrate the feeling even better: “imagine an anthropomorphic dog trying to assure himself that everything is fine, despite sitting in a room that is engulfed in flames”.

Okay. Maybe we should alter our previous interpretation into something more like “crying children and burning bridges”. Now here follow some more metaphorical descriptions of the Van Gent Experience to support said interpretation:

– First up is a more academic formulation: Taking notes in a van Gent class is like writing your own concise history book, accompanied with real-life cartographic illustrations (ahem) and occasional Dunglish slang. As if you’re reading a fancy restaurants’ menu, right?

– One for the car lovers: Taking notes is like racing a Ferrari in a Punto: it’s hard to keep up.

– One for the dreamers: The first thing that came to my mind was how your thoughts can drift off on a Friday class from 16:00 to 18:00, even for a single minute just thinking about what you are going to eat for dinner, and suddenly you’ve missed over a century of information of historical events and 4 personal anecdotes from his life.

– And one for the realists: All I’m trying to do is survive and make good out of the dirty, nasty, unbelievable notes that he gave me.

I’m not making this up, people.

This brings me to the concluding step of analyzing an artwork, the only question that really matters to lay people looking into the value of art will always be: what does it cost?! And I feel like there is only one thing left to say here, as one of my informants also wisely noted: Creation happens in the midst of Chaos. Although an original Van Gent is hard to grasp in the moment of Creation, and although most of his works are watched with eyes full of panic and Chaos. Just like a few of the most famous painters in history: I believe that his notes, too, will turn out to be of a value that cannot be put in numbers to us students later in life, when the artist himself already has passed away.

Gerjanne Hoek, Class of 2018, is a Linguistics, Politics and History major from Bunschoten-Spakenburg, the Netherlands.

One thought on “The Van Gent Experience”