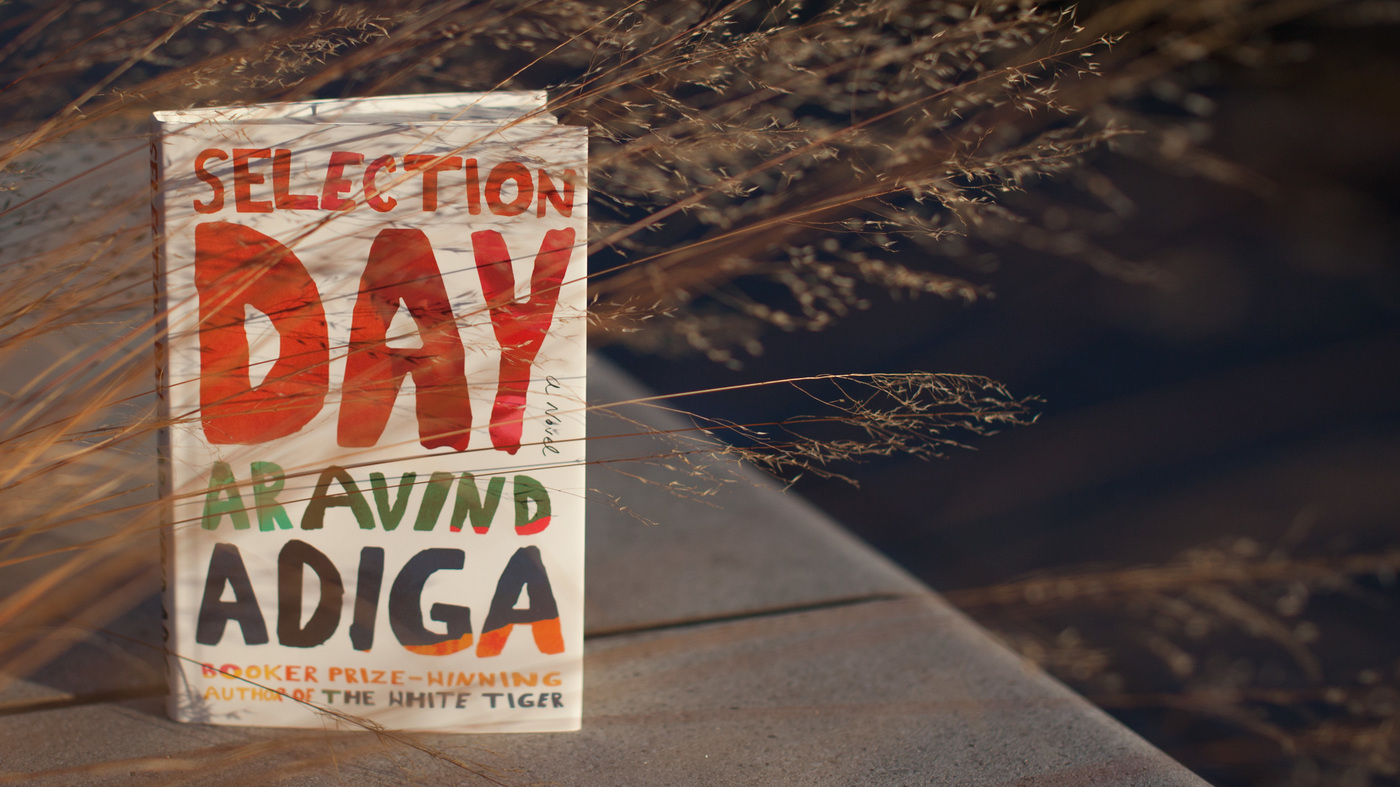

Aravind Adiga’s Selection Day (2016) takes on the challenge of expressing an entire culture through literature, and it does so admirably. The novel, which is set primarily in Mumbai, explores social identity, family relations, and individuality through the medium of cricket. Adiga, who has previously been awarded the Man Booker prize for his lauded 2008 book The White Tiger, shows once more that not only does he understand his homeland, he is a person apt to share it with the world.

The premise is simple: brothers Radha and Manju have one objective, as designated by their overbearing father – to be the best, and second best (respectively) cricketers in the world. While Radha and Manju largely take their father’s commands in stride (their mother is but a memory), his unpredictable violent streak and superstitious obsessions sow the seed for what is to be a gradual rebellion. The story opens at T-minus three years to “Selection Day”, when the Mumbai team is to pick the best youth players from the city.

Radha and Manju grapple with coming of age as individuals while maintaining a brotherly solidarity in face of their father. Anand Mehta, a wealthy expatriate, is back in Mumbai and seeking to embrace his hometown by investing in rising cricket players. Radha and Manju’s father is eager to welcome this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to escape the family’s meager lifestyle. Under Anand Mehta’s help (and conditions), and the seasoned coaching of Tommy Sir, the boys are expected to become stars.

Where Radha and Manju are the hard-training sportsmen from the slums, their peer Javed is slick and wealthy, immediately attracting Manju with his easy rich-boy confidence. As the boys grow and gain exposure to the adult world, it becomes clear that things are not going to play out with ease. Radha, who is the family’s designated winner, pales in comparison to Manju on the field. Manju would rather be studying than playing cricket, and is soon grappling with his homosexual attraction to Javed. Adiga rounds out the cast of characters with Tommy Sir and Anand Mehta, both of which are rich in their own set of failures and unrealized ambitions.

A recurring theme is that of fruitless ambition, both in cricket, and in Indian life more generally. Prominent is the idea that “every man must martyr himself to something: but we have martyred ourselves to this mediocrity (p. 330).” Tommy Sir has spent his life inhaling and exhaling cricket, yet his expertise and authority is undermined throughout. Anand Mehta is an outsider – destined to fail in both the drastically different US and India. As much as Radha and Manju’s father wants them to rise above the social prejudices held against his family, he saddles his sons with enough emotional baggage to prevent them from ever following realizing his hopes and dreams. Manju’s unexpected surpassing of his brother adds fuel to the fire – where ambition brings out the worst in all.

In this way, cricket as a sport is a fitting microcosm – having consequence as a representation of all these issues almost more so than as a game in itself. Adiga frequently describes cricket as a sort of elusive temptress, a game dependent on both order and chaos. No matter how much Radha and Manju are made to practice, this is only one small element of their success, or lack thereof, on the field.

Throughout the story, India and its offspring are presented as highly conflicted individuals, searching for satisfaction, yet chained to the iron ball that is their insatiable desires. Adiga makes it clear that it is little wonder that the country’s prime pastime is rife with elements hinting at this tragic fact.

Noga Amiri, Class of 2018, is a Literature and Art History major from Hilversum, the Netherlands.