by Andrea Undecimo

‘Pink mosque in Shiraz’

When I first told my parents and my friends that I was going to spend two weeks, alone, in Iran, the reactions I received spanned from honest worry for my mental health, to attempts to persuade me not to go, because the place was crowded by religious fundamentalists and terrorist groups. As a Westerner, I would be seen as the embodiment of the enemy, and therefore it was just not safe for me to travel in this area. However, if there is a country where the reality completely defies the clichés and the perception we have of it, that must be Iran.

One of the first things that struck me most about Iran was the hospitality of the people. I heard and read about the legendary hospitality of the Middle East, but, frankly, I didn’t think it to be so warm. At one point, after the thousandth cup of tea that I had been offered by carpet sellers, bank officials and shopkeepers, I asked a guy named Reza what the reason behind this cultural characteristic was. He explained to me that the reason was to be found in history: Iran, or what he called Persia, had been for centuries the crossroads of merchants, intellectuals and religious preachers that travelled between the far East and Europe, bringing silk, spices, gold, pearls as well as ideas with them. Hospitality, as well as the tolerance for other cultures, is somehow codified in their DNA and is an essential trait of their culture.

Now, this picture clashes with the complex reality of contemporary Iran. After the revolution of 1979, Iran has become what is now known as the Islamic Republic of Iran, one of the few surviving theocracies in the world. Non-Muslims don’t enjoy the same freedom they had in pre-revolutionary Iran, women are subjected to wear the hijab, the veil that covers their hair and on top of that the government is trying to exercise a sort of damnatio memoriae on the monuments that point out to the glorious past of the Persian Empire, like the ruins of Darius’ palace at Persepolis, in order to eradicate history from people’s identity. To make matters worse, the government of the Ayatollahs, since the takeover of the Imam Khomeini in 1979, has started a merciless ideological war against the secular enemies, the United States, which in part explains the terrible image that we have of Iran (Saudi Arabia for instance has a record of human rights’ violations which would make even the worst dictators turn pale, but we don’t get the same negative image of the country since the U.S. does rich business with the sheiks).

This total opposition to the influence of the United States in the internal affairs of the country is in part the reason why I decided to visit Iran. The fact that here and there in the world there are still some realities who are resisting the inexorable advancement of the liberal order and of capitalism has always fascinated me. In this sense, much of the cultural habits that are present in Iran can only be explained in terms of a completely different ontology from the Western one. In light of this different way of looking at life and of placing oneself within the world, we can start to understand the different way of lives of the Persians, their different conception of eating, the influence that religion exercises in their life decisions and their system of values. And again, it is only by visiting these places that one can defeat easy mystifications of reality. One will see, for example, a reality where the women in Iran play an important role in the functioning of society by taking care of the household and of the education of the children. Or a reality where the people, despite the differences, will do anything so that you can feel at home while being away. This, in part, is the beautiful reality that can be found if one is willing to go beyond the wrong image that we have of this place.

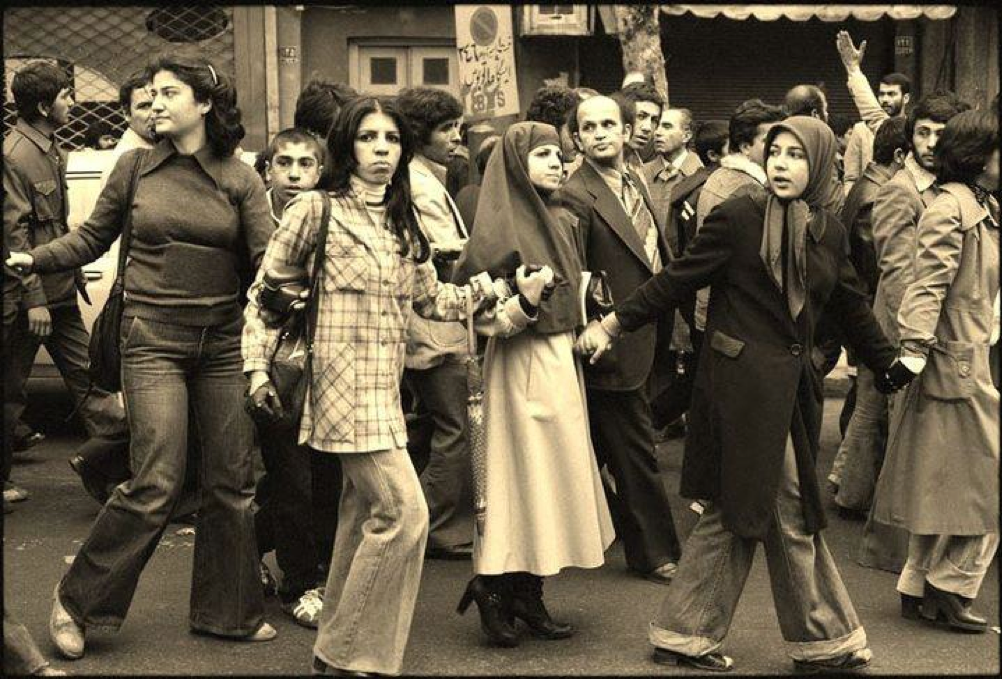

Nevertheless, the dichotomy West-East isn’t enough to understand the intricate situation of Iran. It must be remembered that, before the revolution started, Iran was one of the most advanced countries in the Middle East: the majority of the population was able to go to Europe to study (it is easy to find old people speaking either Italian or French), the authorities had excellent connections with the Western countries and the lifestyle didn’t substantially differ from ours, as can be seen in multiple pictures taken before 1979. In addition to that, a national pride to become central actors in the global system and to break through the isolation that the Ayatollahs have imposed on Iran runs in the country: after all, the heritage of the Persian empire that once dominated the world is still very present and Iran potentially possesses any element, from oil to uranium to gold, to become a central figure in tomorrow’s international scene.

Life before the revolution

In addition to this extremely lively social world, Iran also has to offer some of the most beautiful exemplars of Islamic architecture, like the Shah Mosque in Isfahan with his stunning colourful mosaics and patterns to the very photogenic Pink Mosque in Shiraz, as well as remains of the Persian empire and some of the oldest, still inhabited human settlements in the world, like Yazd. Great food, refined handicrafts and the already mentioned Iranian hospitality will be the icing on the cake.

Andrea Undecimo, Class of 2020, is an Anthropology and Law Major from Macerata, Italy.

Sources:

Image sources: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2012/02/comment-iran-then-and-33-years-after-the-revoltion.html