By Marije Huging

There was once a man who, one night between the main course and the sweet at a dinner party, went upstairs and locked himself in one of the bedrooms of the house of the people who were giving the dinner party.

There was once a woman who got locked up in a mental asylum, only to be saved by her nanny in a submarine.

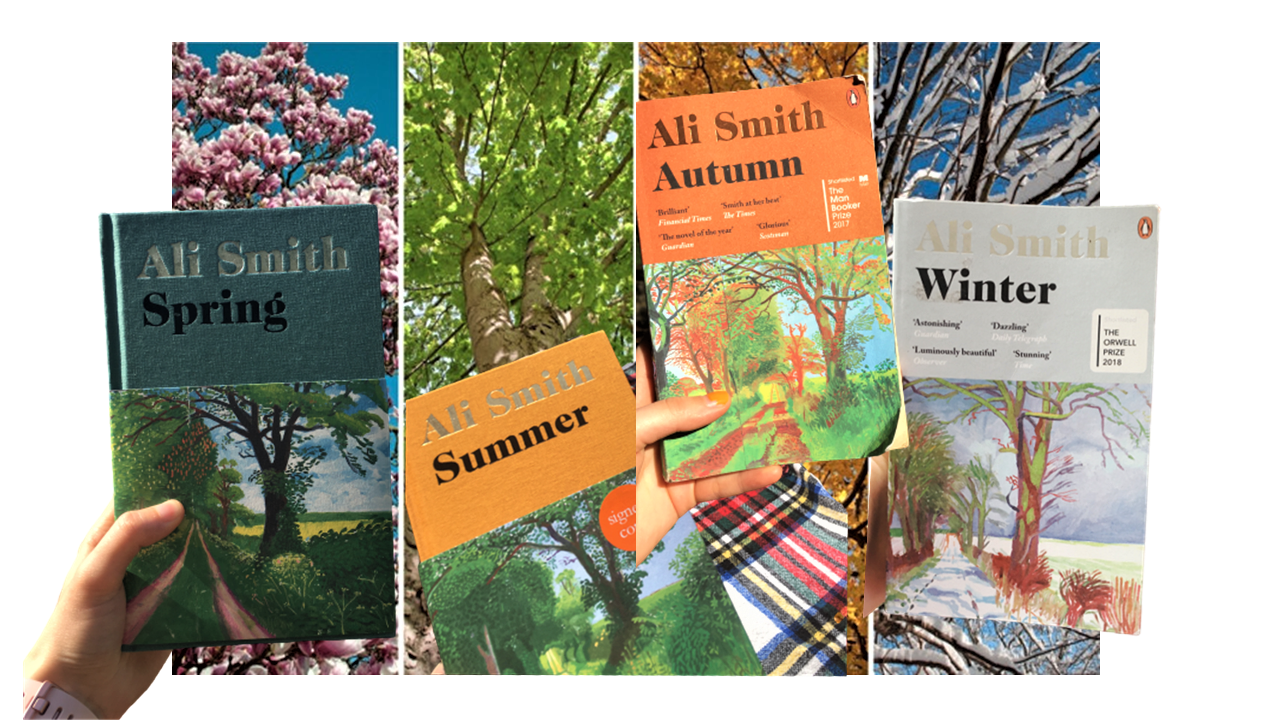

Ali Smith, the writer of the first fragment, most recently published her seasonal quartet of books that were written to directly comment on the world we live in right now, after Trump and Brexit. Whilst those books are great, this winter, I decided to go back and pick up one of her books from ten years ago, ‘There but for the.’ It centers around a man, Miles Garth, who attends a fancy dinner party given by Gen and Eric (get it?!) in the suburbs one night and subsequently locks himself in one of the rooms upstairs, not to come out again. However, more so than actually being about Miles, the story focuses on the effect that he and his actions have on the people around him. The book is cut into four fragmented parts, ‘There’, ‘But’, ‘For’ and, unsurprisingly, ‘The’. Each of the sections is narrated from the perspective of a person who is in some way connected to Miles; an old acquaintance, a man who is haunted by his mom, a young girl, and an old lady.

Apart from its cooky storyline, however, Ali Smith is known for her experimental writing and her wordplay which also appear in this book: she is very occupied with semantics- how we use words, and why they matter. Her texts are- dare I say it- ‘postmodern’.Yet, reading Smith, you never get the feeling of having landed in a class on Derrida, it rather feels like reading one big pun. An example is the sheer abundance of knock-knock jokes interwoven in the novel, which of course raise the question: who is there indeed?

Smith’s experimentalism never gets in the way of telling a good story and making it entertaining. There But For The is whimsical and playful and in contrast to some other ‘postmodern’, ‘pastiche’ novels, never takes itself too seriously, whilst saying serious things.

The other fragment above – referring to the nanny and the submarine- alludes, not to the contents of the book The Hearing Trumpet, but to the life of its author, Leonora Carrington. Perhaps better known as a painter than a writer, Carrington is one of the most famous ( female, because sexism) artists of the Surrealist movement of the thirties. Just like the book I read from her, her life was a little wild, to say the least. She escaped the Nazi’s whilst her lover, who was 20 years older, Max Ernst, was not so lucky. Afterward, she escaped a Spanish asylum- previously mentioned- and hastily went to Mexico, where she stayed, married a poet, and contributed greatly to its women’s movement in the seventies.

The Hearing Trumpet is perhaps Carrington’s most well-known literary work, and it connects nicely to There but for the, partly since Smith calls it ‘One of the most original, joyful, satisfying, and quietly visionary novels of the twentieth century in its foreword, which she wrote 😉 The story is about Marian Leatherby, a 92-year-old woman who’s son and wife send her to a pseudo-Christian women’s elderly home ran by a sir called Dr. Gambit and Mrs. Gambit. She first receives this news after she’s been gifted a hearing trumpet (hence the title) which allows her to eavesdrop on her family’s conversations- including plans to institutionalize her. Arriving at this home, however, things get… strange. The women at this elderly home all have their own, ambiguous pasts, and Marian gets caught up in a web of mysteries- especially surrounding that of a painting of a winking nun that hangs on the wall- ‘the Abbess of the Convent of Saint Barbara of Tartarus’.

This Abbess gets her own – non-linear and fantastical- narrative in the novel, forming a story within a story- and after this, Carrington’s appetite for the surreal really comes to the foreground. I don’t want to spoil too much, but the story includes a murder??, a hunger strike, freedom for the women, Marian being eaten by her double, and to top it off, an environmental apocalypse.

Smith, in the foreword, comments on The Hearing Trumpet, questioning if Carrington chose an elderly female to criticize her image as a femme-enfant, a term connected with the Surrealist movement that connotes a child-woman, who, because of her innocence and youth, which was believed to help you get closer to your unconscious. In the novel, notably, patriarchal power structures are criticized and broken down completely in favour for freedom and absurdity. However, this celebration of the feminine does not rely on some sort of essentialism; rather, conventions of gender are transgressed and deemed as non-important as a whole.

In the end, though, what these books mainly have in common, is that they both essentially tackle questions about what people remember, and how people listen, communicate with, and treat each other. In Smith’s work, this is mainly done with wordplay, and in Carrington’s work, this is done by the symbol of the hearing trumpet, and all subsequent surrealist imagery. However, there might be another reason why both of these books resonated with me.Haven’t we all been essentially stuck in a bedroom/ retirement home over the last year? I think we are looking for an escape in our own ways, one of which is books. Why not start with these two? They are both one of the funniest, unique and strange novels I have read in the last few months; and you should read them too.

Image Source: https://kiloranmag.org.uk/ali-smith-seasonal-quartet/