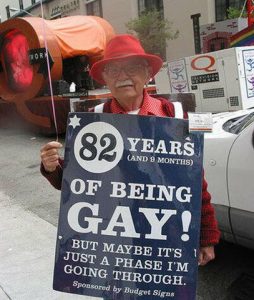

What comes to mind when you think about LGBTQ issues? The gay pride in Amsterdam perhaps, the supreme court granting same-sex marriage to everyone in the US last year, or perhaps just a same-sex couple happily in love? But what about those who spent the greatest part of their lives fighting for same-sex marriage and other rights for the LGBTQ community, in a time that being homosexual was still qualified as a disease? In their case, most of them are now in their 70s of 80s often alone, with a decreasing social network.

In general, sex, sexuality and elderly are topics that we do not hear together very often. Why is that? Imagine yourself growing older, being 70 does not mean that you no longer love, or that you no longer love physically. And within this taboo, gay or lesbian sex is stigmatized even more. Elderly members of the LGBTQ community often feel like they fall between two worlds. They do not feel connected to their generation, but also no longer feel at home in the LGBTQ community. Their generation still embodies the stigma that they experienced as young people. Only in 1973 was homosexuality removed from the list of mental disorders by the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). The World Health Organisation followed even later, in 1992. This means that someone that is now 70 years old and who is from the Netherlands, was seen as mentally ill until they were 28. They had to wait until they were 49 to get legal protection against unequal treatment, and were 56 when in 2001 they were granted the right to marry for the first time. All their lives they have internalized the stigma that was imposed on them, leading to the experience of something called minority stress. This experience is linked to a higher experience of stress, higher depression rates and a higher suicide rate, and is caused by the experience of identity stress, stigma and discrimination (Keheller, 2009).

Now, you would say that at least this group would be able to find solace in their connections with the wider LGBTQ community, and exchange thoughts and feelings with like-minded people. However, the LGBTQ movement and community have surprisingly little attention for their elder members. The ageism that exists in the community often excludes older members from participation, or simply does not include them in the narrative. So, in some sense they have to choose between being stigmatized for their sexuality, or for their age.

Additionally, the older someone becomes, the smaller their social networks tend to become. In the case of these elderly, family networks are often small, since they have often stayed single, or have divorced and no longer have contact with family or children. This poses problems when they become more care-dependent, especially now the Dutch care system is shifting to an approach that focusses on informal care by friends and relatives. That is why policies such as the certifying system of the Roze Loper, which helps elderly homes to create a LGBTQ friendly environment matter. They allow LGBTQ elders to spend their last days in dignity and freedom, in a way that for some was not possible at any other time before. Love, sex and sexuality matter, so let’s break the taboo and allow for all to spend also the last years of their lives in love, dignity and freedom.

Marte Nooijen, Class of 2017, is a Political Science, Law and Anthropology major from Bakel, the Netherlands.

Featured Photo Credit: American Prospect